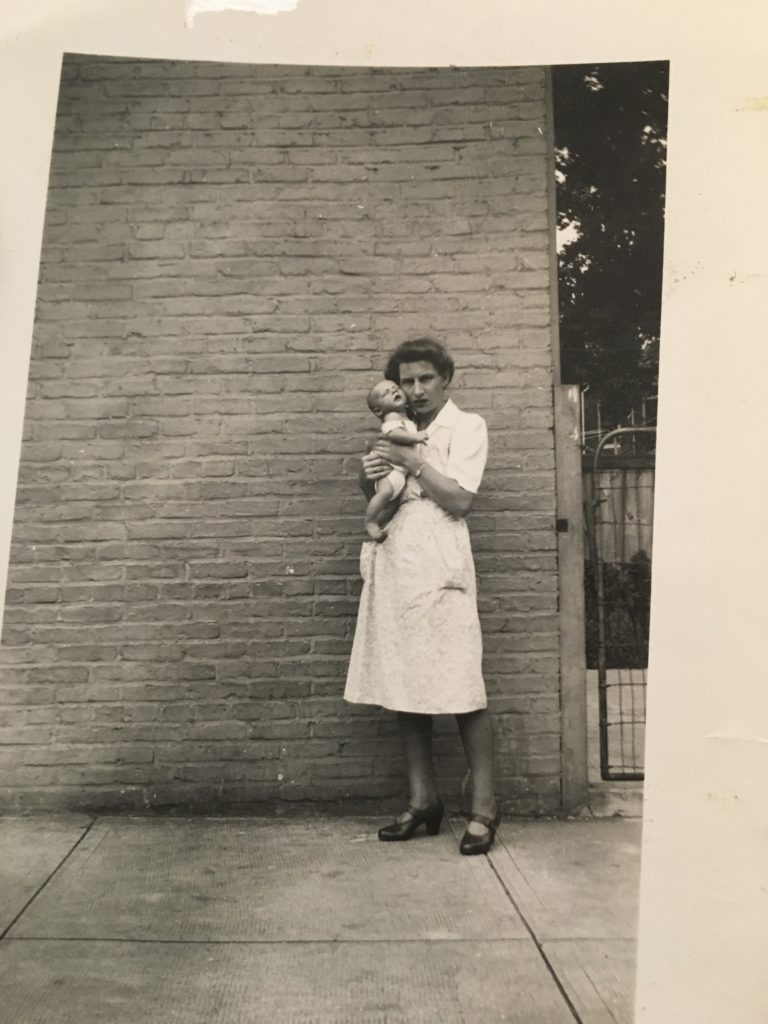

With my dad’s passing, I’ve been thinking a lot about what it means to have knowledge. My dad got his love of knowledge from his mom. My grandmother was universally called a spitfire. When she was diagnosed with a disease that attacked her muscles, her first question was what would happen to her brain. Her doctor said, “Well, in most people, the brain is not a muscle, but that might be different for you, Irm.” She had a tiny body, but she had big hair and big glasses and a big opinions. She was Methodist but often said that she didn’t know why everyone made such a big deal about Jesus, that it was God she cared about. She and her mother once went back to Germany to visit family in the late thirties, and when they refused to say “Heil Hitler,” they had to escape the country under cover of night. She taught me pinochle and let me win and then pretended to be a bad sport about losing, just so I would buy that I beat her fair and square. The only time she ever spanked me was when Bob Barker was on the TV and I told him to shut up. Her father — who was disowned by his father, a German count, because his mother was the housekeeper — literally sold her, as a teenager, to a neighbor to do housework, while committing her mother to a psychiatric facility. Because of this backstory, she vowed that her children would get every opportunity that she did not. And she succeeded. My dad went from the German ghetto in Glen Burnie, Maryland to semi-military school to Yale and then to Harvard. My grandmother, I think, was convinced this freedom would come through knowledge. She was convinced, I think, that maybe the way back into the castle was through the ivory tower.

Once, when we were driving down I-25 when she’d moved to Colorado to be closer to me and my dad, she saw a bumper sticker that said, “He who dies with the most toys wins.”

“That’s wrong, so wrong,” she said. “It’s he who dies with the most knowledge wins.”

This whole nightmare has been hard for a lot of reasons, but most of all, it’s been hard because of the not knowing. I will never know if my dad died of COVID-19 or Alzheimer’s-related complications or both. I will never be able to know what he would say about all the things I found in his basement: letters to old lovers and threatened lawsuits to Random House and a folder full of notes on experiments he and my mom performed on me as an infant (not BF Skinner-style, Piaget style, but still). I’ll never know how he managed to battle his way to the top of his field while almost universally being regarded as a kind man — kindness and success do not, in my experience, often go together, though of course there are exceptions. And on top of all that, of course, there is so much unknown about what will happen with me and with our society: when, if ever, we will open up again.

My dad died with a monumental amount of knowledge that he never had the chance to share with me, and this, somewhat selfishly, is what makes this grief so hard. He died with knowledge about my past that I will never get back, and he died with wisdom about how to live that I’ll never be able to listen to and decide whether or not I agree with it. It’s both of our faults: we didn’t know how to negotiate masculinity together. We didn’t know how to get over some fights that happened when I was a teenager. And then he got Alzheimer’s, and he couldn’t negotiate much of anything.

But what I’m understanding at this point is that knowledge is about as useful when you die as toys are. What matters is honesty. What matters is talking to the people around you while you can. What matters is telling the truth when you have the chance. I would give anything to have one more afternoon with my dad, when he was in full control of his facilities, to ask him about all of these parts of his life he never shared with me. But I don’t get that. So what I get to do now is get comfortable in not knowing.

Maybe being comfortable with not knowing is just another way of saying wisdom. Maybe, after all this, I’ll be a little more heartbroken, and a little bit wiser.

Recent Comments